Every security alert comes with a risk score. Unfortunately, your vendors each have their own risk score scale.

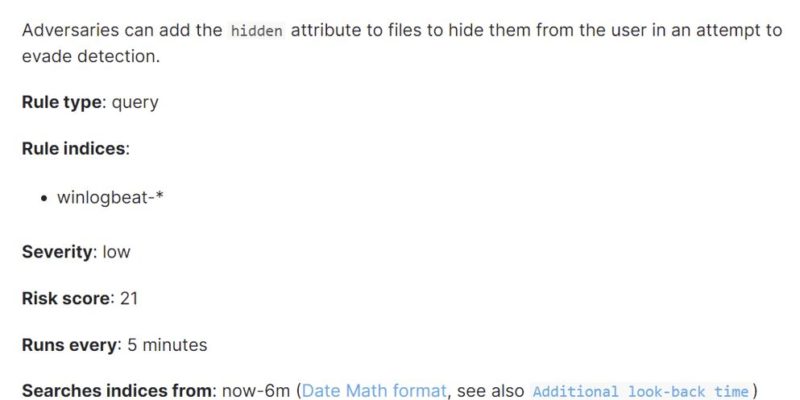

If you use Elastic SIEM, the risk score ranges from 0-100. The following example on “Adding Hidden File Attribute via Attrib” is marked as risk score 21.

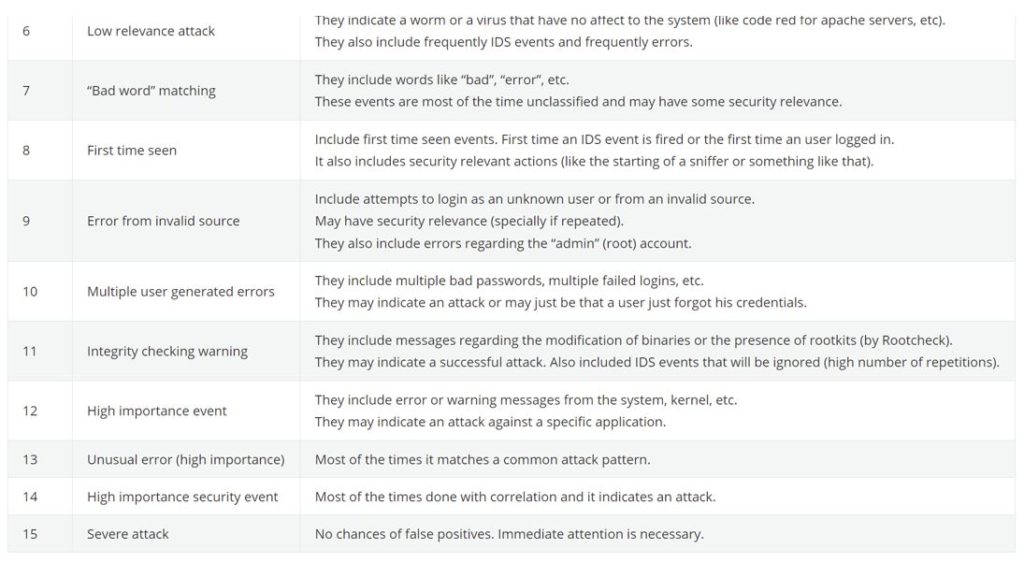

In Wazuh, the alerts are classified into very different levels. The following is a list of risk score for different tier of security alerts generated by wazuh.

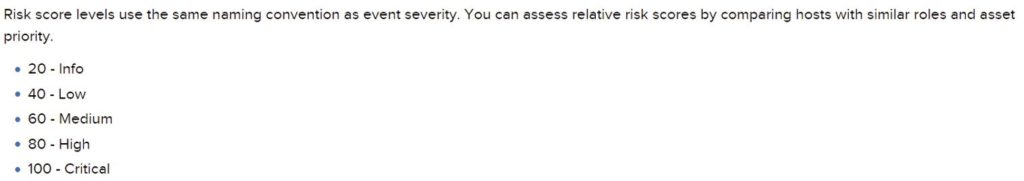

Splunk has a risk score from 0-100, relevant to pre-defined risk levels. (see the following risk level defined in splunk)

And those are just three examples. I could probably bore you to tears with a lot more examples from other vendors, each having different risk score methodologies. Fortunately, most of the time, the risk score associated with security alerts aligns somehow with how likely the alerts is a true positive. While these risks scores are useful, they are not sufficient on their own. Here are some of the challenges:

1. Security risk score are not normalized

Imagine if your kids school decided that each class was going to be graded differently. Let’s say Math was on a scale from 1-100, English was scored with As, Bs, C’s, D’s and F’s with A being the best grade, the closest equivalent to an A in Science was an S grade, and language classes used roman numerals. Ok, anybody confused yet? Based on this, it’s no surprise that security analysts can easily get confused from time to time with the different risks scores they get from their many different vendors And even if they don’t get confused, there’s certainly an impact on the efficiency of the analyst that already has too many alerts to review every day.

2. Security Risk Scores are often too generic and therefore not very accurate

Unfortunately, the person that defined the risk scores that Analysts use, don’t know us or our environment. The risk scores are most often defined when analysts are creating the rules, and that may have been many years ago, at a time when the threat landscape was quite different Some may be based on historical data analyst have. Most are based on intuition from the rule writer. It’s probably not well defined based on your environment, nor is it updated as often as the underlying risk changes. Additionally,

- It has no idea on whether the impacted user is your CEO or not.

- It has no idea on whether this attack is related to your industry or not.

- It has no idea whether you have already identified it as false positive or true positive.

- It has no idea about whether this brute force attack is related to your phishing attack (both of which would be high false positive with low risk score).

All this renders generic risk scores much less accurate and therefore less useful.

3. Security alerts are not security incidents. Single security alert risk may be low, but could represent the occurrence of a low and slow attack.

Half of your security alerts may be false positives. Yet lots of real attacks come from low risk alerts.

It’s not uncommon to miss risk that’s indicated by a low scored alert, or to spend too much time on alerts that further investigation results in their being deemed false positive alerts. So not only does a single alert with a high risk score infer that a security incident is occurring, but also a security events can be easily missed in a number of a low scoring alerts. Security risk could aggregate over time, over multiple alerts that are more meaningful as a group over time, in identifying a security incident. It’s no wonder why there’s so much alert fatigue in cybersecurity.

DTonomy’s patented technology takes input from your many different detection systems and enable security team to use a single normalized risk score. Additionally, DTonomy’s patent technology automatically correlates your security risks and aggregates them into a meaningful risk score by combining security risks together. It even takes your feedback, from your determination of earlier alerts, to dynamically adjust the risk score to make all alerts more relevant to your environment. This automation customizes the normalized and grouped risk scores you get, based on the evolving context of YOUR environment. Imagine not having to review the same false positive day after day, when you know from previous investigation that it’s a regular occurring alert. By aligning risk scores to your environment in this way, DTonomy’s automation makes security scores more valuable and helps Analysts to streamline their investigative efforts. The cybersecurity experts are in high demand today, because their skills are in high demand. DTonomy maximizes the work of these experts thru this automation of a closed loop system to help teams better manage your security risks.

Make security risk score truly powerful to help you better prioritize and identify true security incidents. See It in action.